THE NEW NOSTALGIA

An exploration of nostalgia and how to use it as a force for progress

When it comes to culture, the past has always been a source of comfort and inspiration.

But for a whole new generation, a recent fixation on late ’90s and early '00’s aesthetics is a shocking first experience with the cyclical nature of art and nostalgia. It is their own voices echoing that of their parents— some variation of the “I had that exact same shirt/jacket/hat, etc. at your age,”. They are getting an almost prophetic glimpse at their own cultural mortality, the fetishizing and morphing of their own childhoods into nostalgic adornments for the next generation.

Is this a bad thing, this obsession with the past? Is it a hindrance to progress? The truth is that there is nothing intrinsically negative about nostalgia. It is theorized, in fact, that nostalgia was an evolutionary tool of our ancestors— a means of thinking back to warm, happy memories as a way to maintain psychological comfort under duress, and help contribute to their desire for survival.

But the nostalgia of now seems to be pervasive. The internet has made so much of the world a click away. Not only are the music, movies, and fashion of our past readily available, but our personal history can be accessed within seconds thanks to nearly two decades of social media documentation. The last year has accelerated things, with the majority of us stuck in our homes with very little else to do but steep ourselves in the past and wax nostalgic about better days.

Without a doubt, culture addressed nostalgia long before the pandemic, with varying degrees of success. You only have to look at the movies of the past decade - the endless rebooting of old, tired franchises- to see how the monetization of nostalgia can be detrimental to the long-term growth of a medium. Simultaneously though, Artist Kehinde Wiley is celebrated for his depictions of contemporary African American subjects rendered in historic and classical western European styles, taking advantage of the nostalgia of classical western art to raise the stakes on his own subject matter. Musical artists like Kevin Parker and D’Angelo have made careers of turning sonic nostalgia on its head, simultaneously progressing the medium forward while relying on resonance with the past.

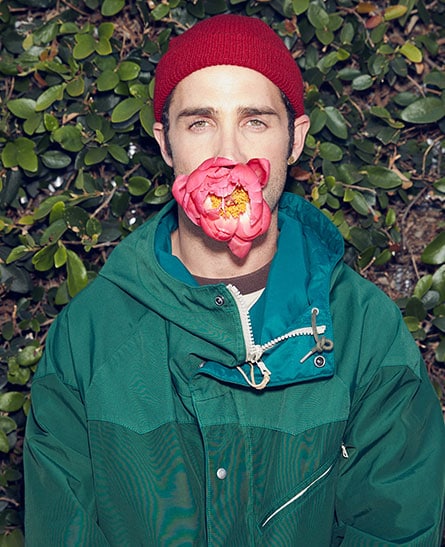

Fashion, too, is seemingly always tinkering with getting it’s nostalgia and progress formula just right.

Balenciaga’s Triple S sneakers are an example of the forward motion that can be brought on by nostalgia, they quite obviously reference the slightly oversized, almost out of place feeling sneakers of the ’90s, but then build upon it with a maximizing of its features, accentuating the radius and arch of the sneaker in an almost irreverent celebration of our growing infatuation with footwear.

To many, the iconic Burberry check is another nostalgic piece, something from a more ‘sophisticated’ era of menswear that is celebrated for its heritage. Riccardo Tisci has managed to bring that iconic motif into a new context, incorporating it into avant-garde streetwear pieces and recontextualizing what the Burberry check means to the audience of today while still maintaining its place in the cultural heritage.

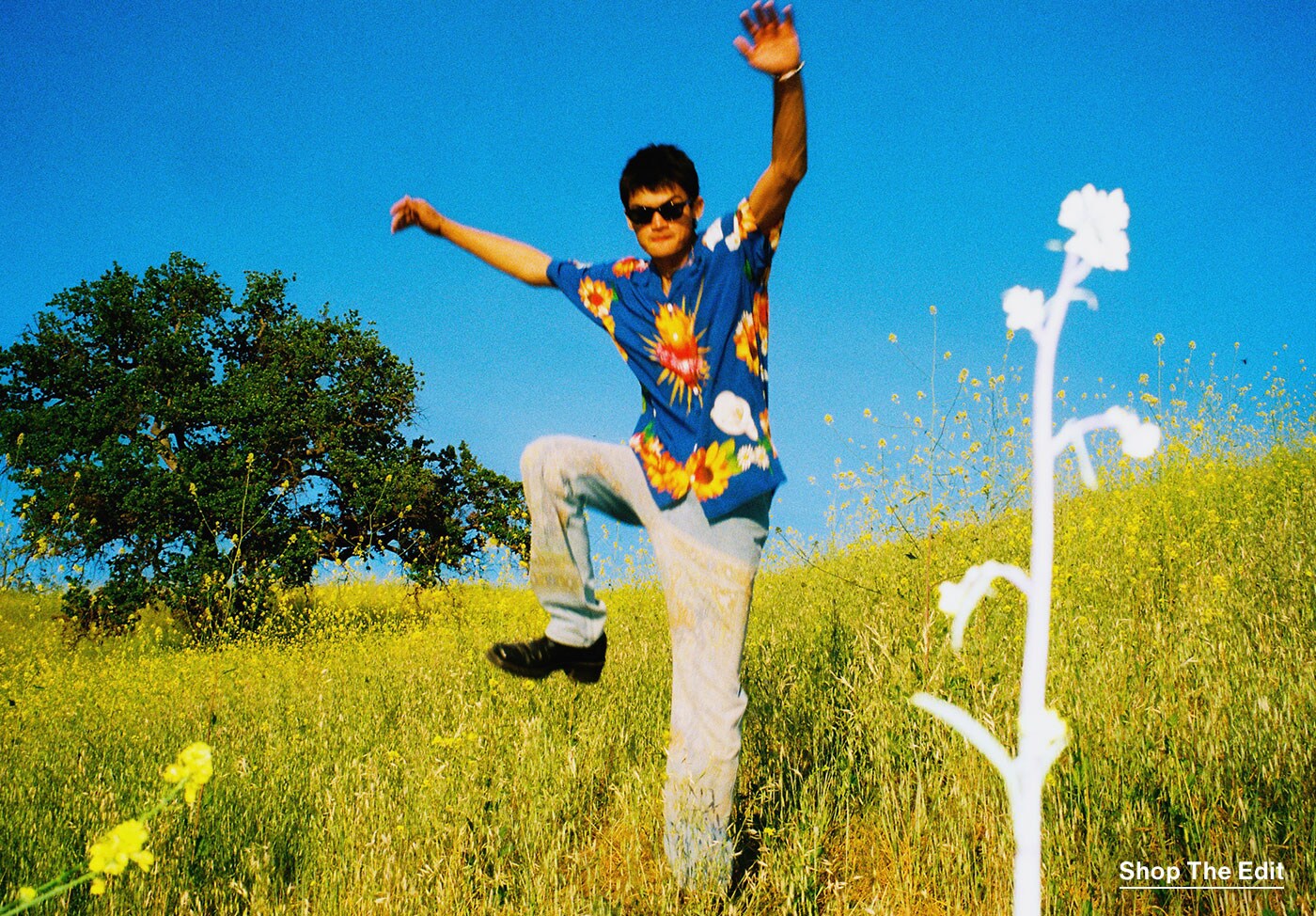

Pleasures, whose ethos is seemingly rooted in nostalgia, isn’t defined by it. The brand often references ideas and concepts of the past, but reimagines them to exist within the cultural milieu of today.

So how can art/design/fashion exist without nostalgia? We don’t think they can. All of us are a product of history and so history will always inspire the things we do and create, but the true value of nostalgia is in using it as a part of a whole, a reference to a previous time which evokes emotion, but implemented into new innovations and ideas that build upon the subject matter and push the medium forward. Fashion is uniquely poised for this. More limber than film and more decentralized than art. Nostalgia, now more than ever, should be used as a tool for progress in the way we dress.